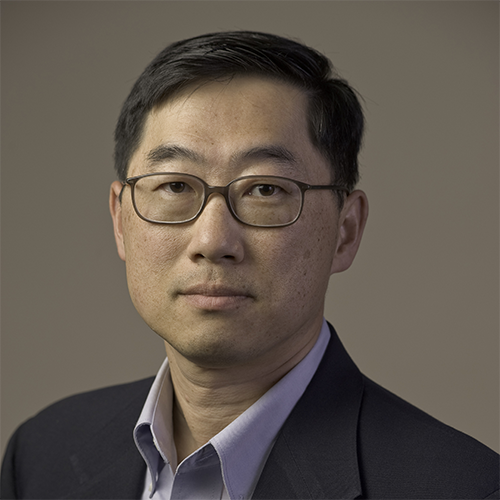

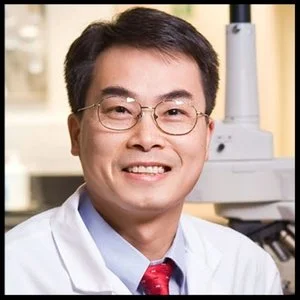

SDRC New Member Spotlight: Dr. Danny Chou

“A game changer” is how SDRC’s newest member, Dr. Danny Chou describes the development of Smart Insulin, a type of insulin formulation that can maintain normal blood sugar levels without the accompanying risk of hypoglycemia. A chemist by training, Dr. Chou is deeply interested in pursuing the development of therapeutically useful insulin analogs for type 1 diabetes (T1D).

In April, 2020, Dr. Chou joined the Stanford faculty in the Department of Pediatrics in the School of Medicine, and also became a member of the Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC). He is excited to join the Stanford and SDRC community of researchers, noting, “The depth and breadth of research is a highly attractive force for my group. Particularly, we are excited about the potential for collaborations, including with the closed-loop insulin delivery team [led by SDRC members Bruce Buckingham, David Maahs – the associate director of the SDRC, Darrell Wilson, Korey Hood, and others] to evaluate some of the novel insulin analogs we are working on”.

The SDRC had a key role in bringing Dr. Chou to Stanford. After an initial meeting at a research seminar, Seung Kim – the SDRC director - invited Dr. Chou to present his work in the regular SDRC research seminar series, and in the Department of Medicine’s Endocrinology Grand Rounds in 2018. This helped to lay the groundwork for building collaborations with SDRC members, and helped convince Dr. Chou make the move to Stanford. “[Stanford] is a fantastic playground for a chemist like myself to make impacts to improve the daily life for people with T1D by developing new insulin therapeutics”, Dr. Chou says.

Dr. Kim states, “Danny Chou is a world-class chemist and insulin biologist, an unusual and potent combination of expertise. We have benefitted working with him in multiple areas, using systems like pigs and fruit flies. We are delighted and fortunate to have him join the Stanford community.”

“I had an opportunity to work on pancreatic beta cells earlier in Graduate School and have fallen in love with the field of beta cells and insulin since”, says Dr. Chou. Prior to joining Stanford, Dr. Chou led a research group at the University of Utah that focused on using protein engineering approaches to create novel therapeutics for T1D patients. Currently available insulin analogs in the market, of course, have many benefits. “Still, it takes huge efforts for people with T1D to manage their blood sugar within the optimal range because of the difficulty to decide the “perfect dose” of insulin”, notes Dr. Chou. This ‘still imperfect’ aspect of insulin replacement is a key motivation for Dr. Chou’s research efforts.

Dr. Chou’s quest to perfect insulin analogs led him into the fascinating and strange world of predatory fish-hunting snails, a group of marine animals that paralyze their prey with venom that contain an ultra fast-acting insulin. “In this particular case, we were inspired by a class of venom insulin molecules with (unique) features. This led us to identify a new linkage to introduce an additional chemical bond to stabilize the insulin conformation without sabotaging potency”, he explains. The report of this novel insulin was widely heralded in the research community. In the world of diabetes care, the development of this ultrafast-acting insulin analog would be another ‘game-changer’, says Dr. Maahs.

Dr. Chou’s work stresses the importance of basic research in providing fruitful (but unforeseen) foundations for clinical applications. “Our fundamental studies on venom insulin have led to several projects for novel insulin therapeutics, which truly demonstrates the value of basic science research”. A portion of Dr. Chou’s group also studies insulin receptor signaling pathways with a specific focus toward understanding the pathways impacted by insulin binding to its receptor. “It is crucial to study whether the mutations on potential insulin analogs may impact the signaling and whether the receptor conformation differences can guide future therapeutic development”, he says.

Dr. Chou's research program has been recognized through support from a JDRF Career Development Award, a Vertex Scholar Award, and an American Diabetes Association (ADA) Junior Faculty Award. His laboratory has received support through grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Department of Defense, JDRF and ADA. Once they complete their move and transition to Stanford, Dr. Chou and his team will work in the Grant Building Research labs.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a Science Writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

SDRC Trainee Highlight: Dr. Laya Ekhlaspour

SDRC applauds the achievements of its outstanding trainees and is committed to supporting their growth via Pilot and Feasibility grants, opportunities to showcase their work in weekly SDRC seminars and providing a collaborative environment across disciplines. Here, we are proud to highlight the work of SDRC member and Instructor, Pediatrics - Endocrinology and Diabetes, Dr. Laya Ekhlaspour who was recently awarded an SDRC Pilot and Feasibility Grant with generous funding support from the Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI) and the Department of Pediatrics at Stanford.

Dr. Ekhlaspour is interested in improving the effectiveness of artificial pancreas systems for type 1 diabetics. Current artificial pancreas systems lack the ability to automatically detect meals because of which patients often find it challenging to control their blood sugar levels after meals. Dr. Ekhlaspour’s project will track the effect of fat and protein in the diet on blood sugar levels after meals. “This information could be used in artificial pancreas systems to improve glycemic control without meal announcement”, she says.

To figure out the impact of specific food groups on postprandial sugar levels, Dr. Ekhlaspour will first conduct an analysis of well-defined meals with known glucose, protein and far content using “existing datasets of CGM and insulin values in closed loop systems”, she explains, saying “This analysis will provide data to allow modeling for insulin requirements, and eventually setting the percent of insulin required upfront for different kinds of meals”, essentially paving the way for a smarter artificial pancreas.

Technical challenges aside, Dr. Ekhlaspour also recognizes the other issues that patients face when it comes to using artificial pancreas systems, including current hybrid closed loop systems which, she acknowledges, “requires additional inputs and pre-meal insulin dosing calculations to reduce postprandial hyperglycemia”.

The initial phase of Dr. Ekhlaspour’s proposal is supported by SDRC. SDRC members Drs. Bruce Buckingham and Manisha Desai will serve as her primary mentor and co-mentor respectively for this project. Speaking of her commitment to improving artificial pancreas systems, she affirms, “My long-term goal is to decrease the diabetes burden so that patients do not have to count carbs, fat or protein”.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

SDRC MEMBER PUBLICATIONS ROUNDUP

Here we highlight SDRC member publications and celebrate their scientific accomplishments and progress towards the development of innovative strategies to treat and cure diabetes. The SDRC is committed to supporting its members and their research through technical resources, training and opportunities for collaboration. The studies published by our members (in bold) listed below were directly supported by the SDRC.

Poon AK, Meyer ML, Tanaka H, Selvin E, Pankow J, Zeng D, Loehr L, Knowles JW, Rosamund W, Heiss G. Association of insulin resistance, from mid-life to late-life, with aortic stiffness in late-life: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020; 19:11.

Prahalad P, Addala A, Scheinker D, Hood KK, Maahs DM. CGM initiation soon after type 1 diabetes diagnosis results in sustained CGM use and wear time. Diabetes Care 2020 Jan;43(1):e3-e4.

Sato S, Suzuki J, Hirose M, Yamada M, Zenimaru Y, Nakaya T. Ichikawa M, Imagawa M, Takahashi S, Ikuyama S, Konoshita T, Kraemer FB, Ishizuka T. Cardiac overexpression of perilipin 2 induces atrial steatosis, connexin 43 remodeling, and atrial fibrillation in aged mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019 Dec 1;317(6):E1193-E1204.

Han L, Bittner S, Dong D, Cortez Y, Dulay H, Arshad S, Shen WJ, Kraemer FB, Azhar S. Creosote bush-derived NDGA attenuates molecular and pathological changes in a novel mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2019 Dec 1;498:110538.

Razavi M, Zheng F, Telichko A, Ullah M, Dahl J, Thakor AS. Effect of pulsed focused ultrasound on the native pancreas. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020 Mar;46(3):630-638.

Wiromrat P, Bjornstad P, Vinovskis C, Chung LT, Roncal C, Pylse L, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ, Cherney DZ, Reznick-Lipina TK, Bishop F, Maahs DM, Wadwa RP. Elevated albumin secretion in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019 Dec;20(8):1110-1117.

Allegretti PA, Horton TM, Abdolazimi Y, Moeller HP, Yeh B, Caffet M, Michel G, Smith M, Annes JP. Generation of highly potent DYRK1A-dependent inducers of human beta-cell replication via multi-dimensional compound optimization. Bioorg Med Chem. 2020 Jan 1;28(1):115193.

Miller KM, Beck RW, Foster NC, Maahs DM. HbA1c levels in type 1 diabetes from early childhood to older adults: A deeper dive into the influence of technology and socio-economic status on HbA1c in the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry findings. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020 Jan 6 (Epub ahead of print).

Wainberg M, Mahajan A, Kundaje A, McCarthy MI, Ingelsson E, Sinnott-Armstrong N, Rivas MA. Homogeneity in the association of body mass index with type 2 diabetes across the UK Biobank: A mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2019 Dec 10;16(12):e1002982.

Lal RA, Basina M, Maahs DM, Hood K, Buckingham B, Wilson DM. One Year Clinical Experience of the First Commercial Hybrid Closed-Loop System. Diabetes Care. 2019 Dec;42(12):2190-2196.

Ahadi S, Zhou W, Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose SM, Sailani MR, Contrepois K, Avina M, Ashland M, Brunet A, Snyder M. Personal aging markers and ageotypes revealed by deep longitudinal profiling. Nat. Med. 2020 Jan;26(1):83-90.

Wang W, Yan Z, Hu J, Shen WJ, Azhar S, Kraemer FB. Scavenger receptor class B, type 1 facilitates cellular fatty acid uptake. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2020 Feb;1865(2):158554.

Azhar S, Dong D, Shen WJ, Hu Z, Kraemer FB. The role of miRNAs in regulating adrenal and gonadal steroidogenesis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020 Jan;64(1):R21-R43.

Kim S, Whitener RL, Peiris H, Gu X, Chang CA, Lam JY, Camunas-Soler J, Park I, Bevacqua RJ, Tellez K, Quake SR, Lakey JRT, Bottino R, Ross PJ, Kim SK. Molecular and genetic regulation of pig pancreatic islet cell development. Development. 2020 Feb 27. pii: dev.186213.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

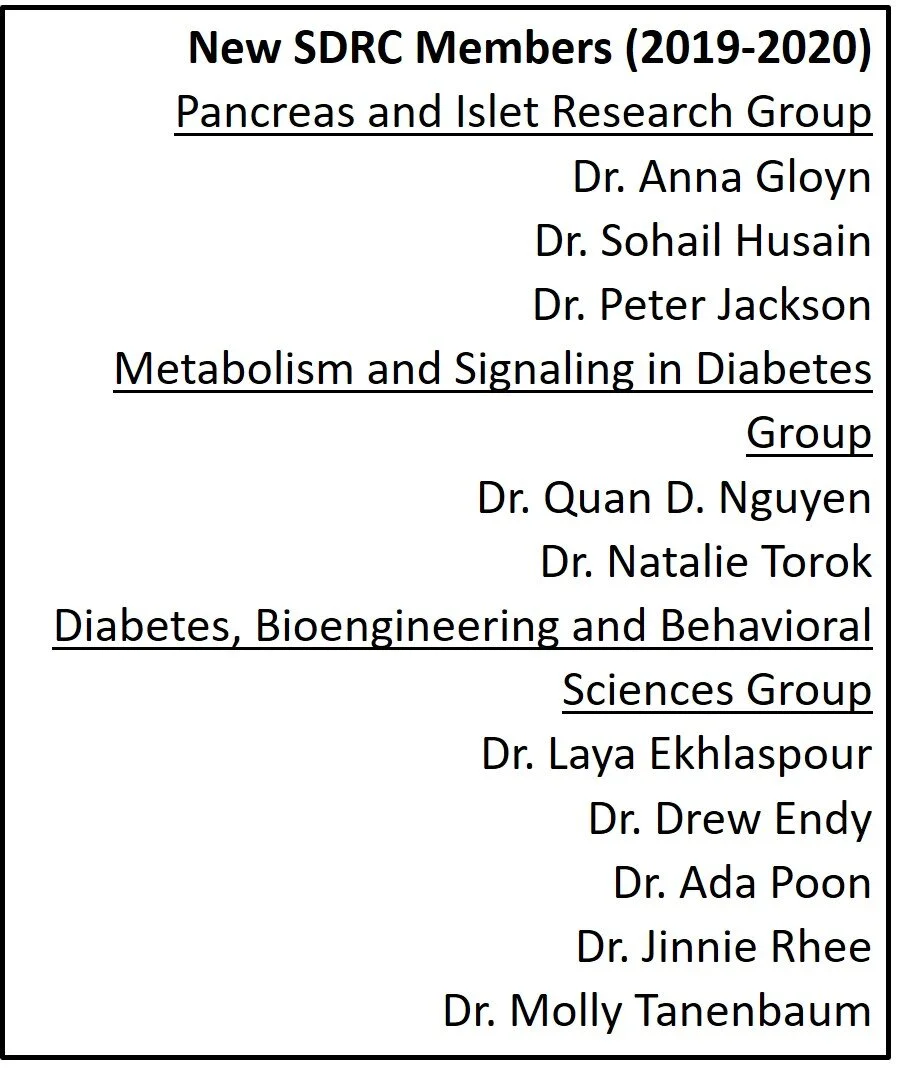

Director's Message

I am happy to invite you all to the first anniversary edition of the Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC) newsletter! I’d like to start by extending a warm welcome to our newest SDRC members which include outstanding young investigators as well as world-renowned leaders in the field. SDRC treasures and thrives on the rich, collaborative environment fostered between its brilliant researchers who support our core mission of promoting innovation in diabetes research via multidisciplinary research partnerships. In the coming months, we anticipate bringing even more investigators into our community which is already 105 strong.

SDRC members have a robust track record of achieving world-wide recognition with their groundbreaking research studies, most recently exemplified by Dr. Kenneth Mahaffey, Professor of Cardiovascular Medicine at Stanford who was a recipient of the 2020 Top 10 Clinical Research Achievement Award for his recent clinical study ‘Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy’ published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

I’d also like to use this opportunity to highlight the recent development of the SDRC Tissue Core under the umbrella of the SDRC Diabetes Clinical and Translational Core for the benefit of our new and existing SDRC members. The SDRC Tissue Core provides researchers with unprecedented access to a wide range of precious human donor tissues via a simplified, low-cost procurement option thanks to the efforts of Dr. Walter Park and Sharon Pneh.

The 4 core facilities of SDRC, The Islet Research Core managed by Dr. Yan Hang, the Clinical and translational Core managed by Christina Petlura and Sharon Pneh, the Genomics and Analysis Core run by Drs. Hassan Chaib and Ramesh Nair, and the Immune Monitoring Core led by Dr. Kent Jensen form an essential backbone of support for SDRC researchers in terms of providing technical expertise and training as reflected by their vibrant use by SDRC members and their contributions towards grant applications and in over 30 published papers in the last year alone.

The SDRC is committed to providing training and outreach opportunities to its younger investigators and trainees. In this context, I am pleased to report that several faculty members availed themselves of the recent SDRC Faculty Grant Writing Course which resulted in the successful funding of 15 grants including RO1, UO1, RO3 and R35 grants. The success of the course prompted us to conduct a second session in January 2020 which was well attended by a diverse group of investigators.

I am proud to bring your attention to the recently launched multidisciplinary Stanford Pancreatic Islet Transplantation and Immune Tolerance (SPIRIT) program spearheaded by an exemplary team of SDRC physicians and researchers in conjunction with Stanford Health Care. We anticipate that this program will be instrumental in promoting research and clinical efforts centered around immune tolerance and islet regeneration.

I am also honored for the opportunity to lead the new Northern California Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) Center of Excellence (COE) with Dr. Mathias Hebrok at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF). As co-directors of the COE, our goal is to usher in a new era of collaborations between Stanford and UCSF diabetes researchers to develop innovative preclinical and clinical therapeutic strategies for immune modulation and islet regeneration in type 1 diabetes.

Finally, I would like to applaud all of our members, trainees, core facility managers and students for their hard work and dedication to conducting the kind of high-quality, collaborative and multi-disciplinary research that has resulted in over 2000 member publications including 375 collaborative papers and 200 diabetes-related grants, more than 50 of which are ongoing research partnerships between members, since the inception of SDRC. I invite you to celebrate and support our vibrant community at our upcoming 5th Annual Frontiers in Diabetes Research Symposium on May 27, 2020!

Seung Kim, M.D., Ph.D.

Director of Stanford Diabetes Research Center

Professor, Developmental Biology and by courtesy of Medicine (Endocrinology)

Ageotypes: When age is no longer just one number

“Which is aging more, your liver or your kidney?” might sound like a strange question to most of us, however, a recent study by Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC) member and Stanford Ascherman Professor and Chair, Department of Genetics, Dr. Michael Snyder and his colleagues found that your liver could indeed age differently than your kidney.

We know that people age differently from each other. Some sixty-year-olds can run marathons while others develop diabetes. A forty-year-old might have a strong heart but a weak liver. Individual aging parameters such as cholesterol levels or glycosylated hemoglobin are useful clinical indicators but do not explain why aging is so different between people, and even within the same person over time.

“Global monitoring of molecular profiles in the same person has not been performed previously” note the authors, explaining why we don’t have a comprehensive understanding of how different pathways change in a person as they age. Dr. Snyder’s group conducted the first in-depth global analysis of over 100 molecular markers in prediabetic and healthy people from 29-75 years of age over the course of 2-3 years. The study revealed distinct aging patterns or ‘ageotypes’ within 4 biological pathways: immune, metabolic, liver and kidney function.

“We found that people age along different pathways and at different rates, something that the aging field is just beginning to appreciate”, says Dr. Wenyu Zhou, co-first author of the paper. For example, the researchers identified individuals with an immune ageotype who had an increase in immunity-related molecules with age, indicative of an aging immune system. However, they also identified people who showed the reverse immune-response trend with age, that is, a decrease in immunity-related molecules. “Notably, individuals showed distinct and sometimes opposite patterns of expression in molecules and pathways” say the authors, emphasizing the importance of a personalized approach towards assessing how people age.

Dr. Snyder’s team was especially interested in aging differences between healthy insulin sensitive (IS) and prediabetic insulin resistant (IR) people who are unable to process blood sugar efficiently. As expected, IR individuals did age differently from IS individuals – the researchers found 10 molecules that showed significantly different patterns between the IS and IR groups. Of note, many of these molecules represent an immune ageotype, “suggesting”, the authors wrote, “that individuals with IR may experience increased inflammation with age more rapidly than individuals with IS”.

The most exciting aspect of personalized medicine is the potential to improve health by targeting traits unique to the individual. The authors found that in at least a subset of participants, behavioral changes influenced their ageotype. For instance, 4 individuals who had made positive lifestyle changes to their diet or exercise regimens showed lowered glycosylated hemoglobin levels reflecting improved glucose metabolism. Dr. Zhou notes, “Knowing how each individual ages will help devise targeted and personalized interventions to battle age-related diseases”. In this context, the researchers have already filed for a provisional patent titled “Actionable diagnosis of personal aging”.

The work was a massive undertaking in terms of sample collection and analysis with more than 18 million data points generated from 106 patients via multiomics assays to track proteins, microbes, immune molecules, RNA transcripts and standard clinical markers of aging. The authors acknowledge the contributions, funding, bioinformatics and data analysis support from core facilities within Stanford including the Diabetes Genomics and Analysis Core of the SDRC, and the Stanford Center for Genomics and Personalized Medicine run by Dr. Ramesh Nair. Other Stanford co-authors include co-first author Dr. Sara Ahadi, Dr. Sophia Miryam Schüssler-Fiorenza Rose, Dr. M. Reza Sailani, Dr. Kévin Contrepois, Monica Avina, Melanie Ashland and Professor Anne Brunet.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

Diabetes Management: Insulin-dependent diabetics, what are you wearing?

We are pleased to spotlight upcoming Diabetes Technology Symposium workshops conducted by Stanford Health Care in partnership with the Stanford Health Library and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) with support from the SDRC.

The symposium will be an opportunity for the diabetes community to learn about the latest in diabetes technology including wearable devices, apps and data management.

SDRC member Dr. Marina Basina who leads the Diabetes Care Program at Stanford will conduct workshops focused on topics that are directly relevant to insulin-dependent diabetics and their families. The first one, on March 19, 2020 will feature a talk by Dr. Basina, MD and registered nurse, Tara Smith, MS on using nutrition, insulin adjustments and exercise apps to favorable impact blood sugar control and related outcomes. Dr. Basina is also pleased to invite exercise physiologist, Dr. Dessi Zaharieva who works in SDRC co-director, Dr. David Maahs’ group to present her work on March 19 at the symposium, noting, “Dr. Zaharieva has published several studies on exercise and insulin in type 1 diabetes”. Interested people can RSVP here.

Anna Simos, the program manager for the Diabetes Care Program will be coordinating the workshops and is excited about promoting the symposium to help reach and serve as many patients and caregivers as possible. The symposium will also host two additional workshops this year, on July 23 and November 19. The summer workshop will focus on helping patients manage their blood glucose levels by optimizing the amount of proteins, fiber and carbs in the diet. In the Fall workshop, Dr. Basina will discuss ways to harness the data generated by the glucose management system and tailor it to patient requirements.

The SDRC is proud to support the Diabetes community via the Diabetes Technology Symposium. The workshops will be held at the Hoover Pavilion 211 Quarry Road, 4th Floor, Palo Alto CA 94304.

To learn more about the symposium, workshops or to register, please call 650-498-7826 or click here.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

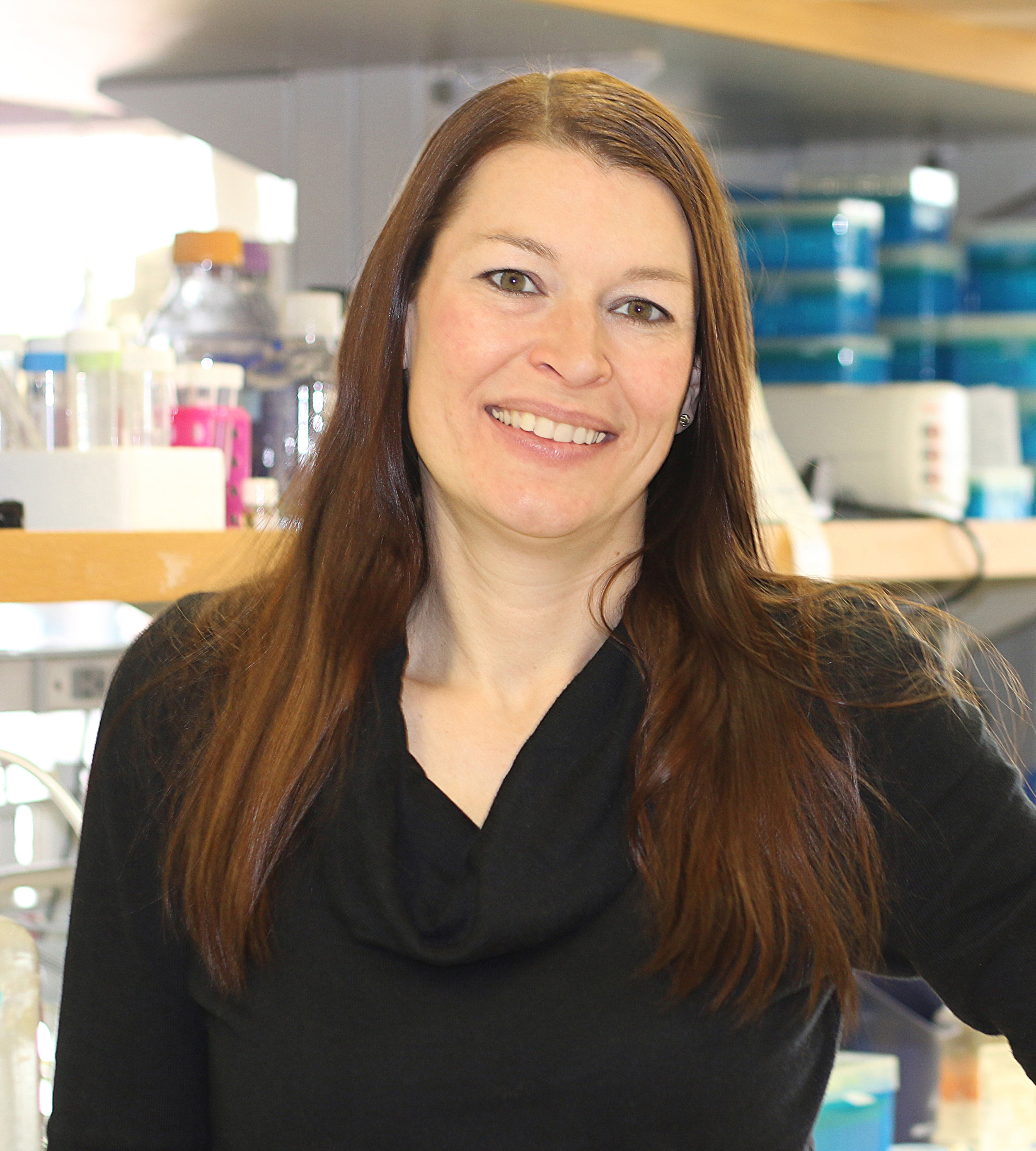

SDRC Member Spotlight: Dr. Anna Gloyn

Dr. Anna Gloyn (left) with graduate student Antje Grotz (center) and postdoctoral researcher, Dr. Nicole Krentz

Stanford Diabetes Research Center is thrilled to welcome its newest member Professor Anna Gloyn who recently joined the Department of Pediatrics - Endocrinology and Diabetes at Stanford. Dr. Gloyn moved to Stanford after 15 years as a faculty member at the University of Oxford, UK and has long been deeply committed to understanding how genetics impacts insulin-producing pancreatic beta-cell function and influences diabetes. She envisions that this knowledge is valuable and, in some cases essential for developing precision medicine approaches to treat diabetes.

Dr. Gloyn’s goal of using genetics as a tool to understand and treat diabetes began with her interest in diabetes as an undergraduate. “I was totally fascinated by the impact the loss of one hormone could have, metabolically”, she says. Her graduate and postdoctoral research focused on the genetic basis of diabetes leading to the discovery of mutations responsible for causing neonatal diabetes, findings that paved the way for superior treatment strategies that targeted the functional impact of the mutation.

Although genetics play an important role in the development and progression of diabetes, Dr. Gloyn is quick to acknowledge the inherent complexity of the disease in terms of its causes. “Our genetics haven’t changed over the last 20-30 years, so the increase in type 2 diabetes that we’re seeing globally has to be attributed to changes in our environment. But what’s important to understand is that genetics is a solid place to start in terms of identifying causal dysfunctional pathways in diabetes which potentially can be targeted therapeutically”, she notes.

Dr. Gloyn is excited about the potential for using the data mined from genetic studies to help develop personalized and integrated approaches to diabetes risk assessment, treatment and prognosis. “There’s a lot of interest in the field to use data that has emerged from global genetic studies to develop risk scores for people in the population that are at a higher risk for developing a specific trait. If you look at 23andMe, they’ve been aggregating data for some time now and are developing their own genetic risk scores based on the genetic data they have collected”, she says. Dr. Gloyn notes recent contributions of prominent researchers in the US and UK, including Dr. Jose Florez and Dr. Miriam Udler (Boston) and Dr. Mark McCarthy and Dr. Anubha Mahajan (Oxford) in assessing whether more effective therapeutic interventions could be devised based on process specific genetic risk scores. She cautions, however, that while this approach is very robust, it likely won’t replace more traditional sources of information such as age and BMI. “Rather,”, she says, “genetics might tell us more about the type of diabetes someone might develop and what drugs they might respond to”.

Speaking of her own recent work on the Zinc transporter gene SLC30A8 in collaboration with colleagues at Helsinki University, where they uncovered rare loss of function mutations which protect against the development of diabetes in a subset of Western Finlanders, she explains that this discovery provided a critical information for efforts to target the zinc transporter therapeutically. “Pharmaceutical companies became interested in SLC30A8 as a target following the discovery of a common coding variant associated with diabetes risk, but it was unclear from rodent and cellular studies whether it was a loss or a gain of function that was associated with diabetes risk. Human genetics has been absolutely crucial in helping them figure out the type of therapeutic agent, agonist or antagonist, that they should focus on developing”.

Asked about the biggest challenge facing the development of precision medicine strategies to treat diabetes, Dr. Gloyn says, “Genetic studies have received substantial funding and resources in recent years coupled with considerable hype about what genetics will deliver. For some progress has been disappointingly slow and as a community we have not achieved the goals we set ourselves. This criticism is understandable but, in my opinion, harsh, considering how long it can take for basic science discoveries to have translational impact. The onus is on the research community to translate the substantial investments in genetics and new knowledge we have generated into improvements in healthcare.”

Dr. Gloyn is delighted about joining the SDRC community at Stanford, saying, “I’m excited about the opportunity to interact and collaborate with scientists who have been approaching diabetes research in similar but not identical ways. I’m really impressed by the diversity of work that’s happening across the campus”. Speaking about the recent “Ageotypes” study (featured in the current edition of the SDRC newsletter) from SDRC member Dr. Snyder’s group, for instance, she says, “It would be interesting to talk to Dr. Snyder’s team about potentially using process specific genetic risk scores to help stratify and identify the types of individuals that he has been studying in his wonderfully complex and innovative study”.

Dr. Gloyn’s team at Stanford includes postdoctoral researcher Dr. Nicole Krentz, and a visiting final year PhD student, Antje Grotz. Dr. Krentz who also relocated from Oxford with Dr. Gloyn recently published a review describing pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction resulting from type 2 diabetes genetics. Antje, a recipient of the Albert Renold traveling fellowship from the European Association for the study of diabetes (EAFSD) is working with SDRC director, Dr. Seung Kim’s group at Stanford.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

Stanford Auto-Islet Transplantation Program and Human Tissue Procurement Program

Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC) member and Department of Medicine (Gastroenterology and Hepatology division) Assistant Professor, Dr. Walter Park, MD also holds the position of Medical Director of the Pancreas Clinic at Stanford Hospital and Clinics. He spoke to us about two new SDRC programs that he is excited about: the Auto-Islet Transplantation Program and the Tissue Procurement Program.

The Auto-Islet Transplantation Program is a part of the broader Stanford Pancreatic Islet Replacement and Immune Tolerance program (SPIRIT). It was set up with the goal of helping a small but significant subset of patients with chronic pancreatitis who suffer from debilitating pain and are thus prevented from living a normal life. In this setting, the patient’s pancreas is removed and islets are harvested for re-infusion back into the patient. “Because this is an autologous transplant, no immunosuppression is required,” explains Dr. Park, adding, “Removing their pancreas is the last resort and it has an 80% efficacy rate for pain treatment. The idea behind re-infusing them with their own islets is to delay the onset of diabetes that would occur as a consequence of removing their pancreas”.

The Auto-Islet Transplantation Program is also expected to benefit researchers who will have access to the residual pancreas tissue. “This is very much a multidisciplinary program” says Dr. Park, noting that in addition to the Pancreas Clinic, the program includes a surgical team helmed by SDRC member Dr. Brendan Visser, SDRC member and endocrinologist Dr. Marina Basina, SDRC member and interventional radiologist Dr. Avnesh Thakor, and SDRC researcher Dr. Everett Meyer to oversee the islet harvesting and organ processing. Other members of SPIRIT include Drs. Stephan Busque, Seung Kim, Rick Kraemer, David Maahs, Bruce Buckingham, Kent Jensen and Catherine McIntyre. “It wouldn’t be possible to do this without their support and involvement” affirms Dr. Park.

Dr. Park who is also a co-founding member of the SPIRIT program adds: “This program has broader implications for diabetic patients in terms of helping support pancreatic islet intervention, regeneration, and immune tolerance efforts at Stanford and providing an infrastructural framework for future islet replacement-based therapies for diabetic patients, including those with type 1 diabetes”.

The Tissue Procurement Program is a service offered by the SDRC Clinical and Translational core facility. “Translational research in Diabetes requires moving beyond preclinical animal models and testing hypotheses on human materials. To this end, we are providing researchers access to freshly procured human organs and tissues” says Dr. Park.

Partnering with tissue procurement organizations such as the International Institute for the Advancement of Medicine (IIAM) and the National Disease Research Interchange (NDRI) has been instrumental in this effort. “These organizations provide human tissue that are unsuitable for transplantation but are nevertheless collected in a fairly rapid manner to allow it to be used effectively for human tissue research” he elaborates.

A number of organs are available through the tissue procurement program including liver, skin, adipose, muscle, pancreas, or any organ that is specifically requested by an SDRC member. The program also allows for the inclusion of donor criteria as a part of the organ procurement process. “We completed our first procurement order for skin and muscle recently. We’re excited about getting this off the ground and we expect there will be more interest from SDRC members” he says. SDRC members who are interested in obtaining human organs may contact Dr. Park or Sharon Pneh (spneh@stanford.edu) who coordinates the tissue procurement effort on behalf of the SDRC Clinical and Translational core facility.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

Type 1 Diabetes Care Program Launch

The Stanford Health Care (SHC) system is excited to announce the launch of a new Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) Care program on November 14th, at the Stanford World Diabetes Day Health Fair, to fulfill an unmet need within their growing community of T1D patients. Dr. Marina Basina who is a clinician heading the Diabetes Care Program run by the SHC system and supported by Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC) resources helps patients manage their diabetes through an integrated and personalized approach to diabetes management. Dr. Basina and Anna Simos, the Program Manager for the Diabetes Care Program shared their vision for the T1D Care Program at Stanford.

“T1D is a 24-hour, 7 days a week, and 365 days a year condition. There are no days off with T1D”, says Dr. Basina, emphasizing that diabetes care is rightly considered to be one of the most psychologically and behaviorally demanding of chronic medical conditions. The SHC Diabetes Care Program which has served more than 2000 patients since its inception, has been nationally recognized since April 2017 and was acclaimed for Best Care practices for Diabetes Self-Management Education by the American Diabetes Association.

So why the need for a program that specifically serves type 1 diabetics?

“Through our Diabetes Care Program, we have found that our T1D patients greatly benefit from having access to an interdisciplinary team of specialists. Although T1D and T2D both have the word ‘Diabetes’ included in their names, they are very different diseases states. We acknowledge the differences between these communities and decided that it was time to recognize the unique needs of our adult T1D patients”, says Dr. Basina.

The primary goal of the T1D Care Program is to work with T1D patients and assist in integrating the latest technology and applied research in nutrition, exercise and proper blood glucose management techniques to align with their life's priorities and improve outcomes. Through the T1D Care Program, patients will have access to diabetes education, management support and continuity of care.

Importantly, the T1D Care Program will coordinate with SHC clinics and partner groups such as JDRF, Beyond Type 1 and Carb DM to seamlessly integrate specific aspects of T1D care such as advocacy, technology, nutritional counseling and education programs tailored to the individual’s needs, referrals and opportunities to learn about and participate in research studies, and collaborating with institutions and organizations to establish islet transplantation programs for T1D patients. “We are fortunate that SHC clinics exist within a community that has robust resources for individuals with T1D”, says Anna Simos.

An individualized approach to diabetes care is a key facet of the new T1D Care Program. While developing and implementing the existing Diabetes Care Program, Dr. Basina learned that a one-size-fits-all diabetes management strategy is not the most effective way to improve patient outcomes. “Instead, we encouraged our patients to identify their own goals through an assessment questionnaire, which in turn provided us with an opportunity to learn about their priorities. This approach has helped create meaningful partnerships with patients and their families to improve outcomes”, she notes.

Speaking about the T1D Care Program Launch, Anna Simos exhorts us to mark our calendars. “We are so excited to announce the launch of our T1D Care Program on November 14, 2019, which coincides with World Diabetes Day and our 6th Annual SHC Wellness Fair!” The Wellness Fair will include wellness screening, education, technology and vendor booths, as well as featuring two celebrity guests. “We are proud to have the opportunity to host Celebrity Chef Doreen Colondres who authored the website The Kitchen does not bite, and Iron Man and World Celebrated Triathlete, Eric Tozer, who made history as the first type 1 diabetic to compete the world marathon challenge and run seven marathons in seven continents in seven consecutive days. We strongly encourage everyone to come and support us!”, she says.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

Northern California JDRC Center of Excellence: Q & A with Co-Director Dr. Seung Kim

The Co-Director of the Northern California JDRF Center of Excellence (COE), Director of the Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC) and Stanford Professor, Dr. Seung Kim, talks about his vision for the Center in developing a cure for type 1 diabetes (T1D).

Congratulations on the launch of the Northern California Center of Excellence! The COE has been established with the goal of accelerating research to develop T1D cures. What specific areas of research will the COE be focused on?

Thank you. We worked very hard with our Stanford, University of California at San Francisco (UCSF), and JDRF colleagues to bring this Center to life. The COE was conceived as a way to develop regenerative therapies for T1D by bringing together an incredibly talented, committed group of researchers from Stanford and UCSF. Dr. Mathias Hebrok, a long-time collaborator from UCSF and I will be heading the COE to address an outstanding problem in T1D pathogenesis: Identifying the basis of autoimmune assault of human islets in T1D and targeting the immune cells to halt this autoimmune destruction of islets. We envision that successful investigations in this crucial area of T1D research will enable translational cell-based replacement therapies and cures for T1D.

A key feature of the COE is its emphasis on collaborative research. What collaborative projects led to the inception of the COE and what future collaborative projects have been proposed?

We’re very proud of the vibrant culture of multidisciplinary collaboration among researchers at Stanford and UCSF which have led to several recent ground-breaking discoveries. Although some may view Stanford and UCSF as historical rivals, we have smashed this notion by building active collaborations between these institutions that have a laser-like focus on a unifying major goal: to cure T1D. Ongoing research partnerships between my group and SDRC member and pioneer in the field, Dr. Judith Shizuru focuses on preventing the body from rejecting donor transplanted cells. Related projects with SDRC member, Dr. Everett Meyer target survival of transplanted cells via immune modulation therapies which forms the basis and central idea for the COE.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from Stanford and UCSF with pioneering expertise in immune biology cell-based replacement therapies will pursue two main projects – one, to identify mechanisms underlying autoimmunity, and two, to suppress autoimmunity and promote graft survival after transplant. In addition to these partnerships, we have built collaborations with Dr. Kyle Loh – my Stanford colleague in the Department of Developmental Biology – and Dr. Matthias Hebrok, my UCSF counterpart in the COE, to improve development of stem cell-derived replacement islet cells. Other projects will be supported by research ‘cores’ that will also bridge and foster collaborative efforts by investigators at UCSF and Stanford.

How has the SDRC supported the ongoing and proposed research for the COE?

SDRC has already been instrumental in providing institutional support to its researchers through a robust framework that nurtures collaboration and a dynamic exchange of ideas between diabetes researchers from Stanford and UCSF. This includes collaboration in the running of its cores (like the Stanford Islet Research Core, which benefits from human islet isolations derived from the UCSF Diabetes Research Center) and through the ‘Pilot and Feasibility’ granting mechanism. In early 2019, SDRC supported the Bay Area Islet Biology (BAIB) meeting that enabled discussions and collaborations between multiple laboratories based at Stanford, UCSF and UC Davis. This has led to work that is now driving forward progress in the COE.

Along these lines, the Stanford DRC and the UCSF DRC will continue working together to build organizational support and maximize collaboration, teaching and mentoring opportunities, and resource sharing through the respective islet cores and access to state-of-the-art techniques and services. Our SDRC Program Manager, Dr. Kiran Kocherlakota has worked day and night to promote institutional partnerships, including with diabetes and transplantation clinics to help build the framework for a translational program. That’s why it’s a natural progression that Dr. Kocherlakota has agreed to serve as a Program Co-manager for the COE.

As Co-Director of the Northern California COE and Director of the SDRC, can you speak to your efforts towards developing an islet transplantation program and the concomitant development of cell-based therapeutics to cure T1D?

Helping to bring a human islet transplantation program has been a labor of love for the SDRC. Recently, we reached a milestone by establishing the Stanford Pancreatic Islet Replacement and Immune Tolerance (SPIRIT) program which was approved by Stanford Health Care. While the SPIRIT program is not yet a part of the COE, our plan is to bring these clinical and basic science programs together in the near future.

The merging of effort by SPIRIT, the COE, and the SDRC will accelerate discovery and application of new therapeutic strategies that will support and enhance the effectiveness of a islet replacement as a ‘standard of care’ for diabetes. For instance, in the COE and SDRC, we are focused on developing immune tolerance and cell-based therapeutics that would dovetail with the overall goal of providing islet transplantation for T1D as well as other forms of diabetes requiring islet transplantation. As Director of the SDRC and Co-Director of the COE, I will work with others to help build organizational and infrastructural support to establish such a cell replacement programs at Stanford.

What is your vision for the COE and its role in influencing the direction of T1D research and therapeutics development?

I envision very promising T1D research and therapeutic strategies as tangible outcomes from the COE that can be introduced to an effective clinical program in the near future. We have an outstanding team across two world-class institutions that will advance our knowledge of T1D disease dynamics and the development of regenerative therapies. We will guide and support collaborative ventures between researchers from Stanford and UCSF by providing an enriching environment in combination with infrastructural support. The COE and SDRC will drive the sustainable exploration of therapeutic strategies to cure T1D.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

SDRC Trainee Highlight: Dr. Mehdi Razavi and Dr. Molly Tanenbaum

SDRC proudly supports its trainees through technical expertise, collaborations and its Pilot and Feasibility grant program. In this issue of the SDRC newsletter, we highlight the research accomplishments of two SDRC trainees, Dr. Mehdi Razavi and Dr. Molly Tanenbaum.

Dr Mehdi Razavi, recently completed his postdoctoral research in SDRC member Dr. Avnesh Thakor’s group and joined University of Central Florida as a faculty member. His postdoctoral research focused on developing novel therapeutic strategies for type 1 diabetes (T1D). Current therapies for T1D include islet transplantation. “However,” says Dr. Razavi, “patients require immunosuppression therapy, which impairs insulin secretion from islets. Hence, a significant proportion of transplanted islets become “glucose-blind”, wherein beta cells still contain insulin granules but cannot effectively release them in response to elevated glucose levels”.

Dr. Razavi’s recent study published in Scientific Reports revealed that pulsed focused ultrasound (pFUS) used therapeutically in the setting of mouse islet transplantation not only enhances islet function and engraftment, but also helps with blood vessel formation which is crucial for graft function. He and his colleagues found that pFUS treatment of islets improved their function by increasing the calcium levels within the islet cells. Dr. Razavi anticipates that transplanted human islets will also be responsive to pFUS treatment. He notes, “Given that pFUS is an FDA approved technology, we believe it has the potential to be easily clinically translated as a completely non-invasive and drug-free therapeutic approach which can be utilized in the setting of islet transplantation”. Although promising, he acknowledges that more studies are needed to assess whether pFUS treatment imparts long-term functional improvement on the islets.

Dr. Razavi’s work was supported by pilot funding through the SDRC’s P30 grant. He plans to explore therapeutic approaches to treat debilitating orthopedic diseases at the University of Central Florida.

SDRC member Dr. Molly Tanenbaum is an Instructor at the Stanford Department of Pediatrics and a Clinical Researcher with a deep interest in improving the lives of people living with diabetes. She was recently awarded a K23 grant to conduct a trial with the goal of helping type 1 diabetics adapt to using continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) via behavioral interventions in line with the 2019 American Diabetes Association Standards of Care recommendations. “There is a need to develop programs that can help support those trying out this technology to increase chances that they’ll get benefits from using it and that they’re able to troubleshoot if any issues come up”, says Dr. Tanenbaum, who also won a 2018 Pilot and Feasibility award sponsored by the SDRC to conduct a pilot study of the behavioral interventions to help T1D patients using diabetes devices.

To design effective interventions, Dr. Tanenbaum and her mentor Dr. Korey Hood surveyed patients and identified cost and inadequate insurance coverage as the most commonly reported barriers to using insulin pumps and CGMs. “As psychologists, we were also very interested in the ‘modifiable’ barriers that could be addressed with increased support or behavioral intervention. We found that the top modifiable barriers were related to people not wanting to wear devices on their bodies all the time” noted Dr. Tanenbaum. Her research also explored the role of self-compassion in managing diabetes and validated a way to measure adult self-compassion specifically in the context of diabetes.

Dr. Tanenbaum is committed to enhancing the quality of life of people with T1D by continuing to assess the challenges individuals face and by developing strategies to overcome them. “Access is definitely the first priority because people with diabetes need to be able to have access to current technology to be able to benefit from it. After that, the next step is thinking about how to best support those using technology such that the benefits of the device (both for diabetes management and quality of life) outweigh the hassle of wearing something on your body all the time. That’s what I’m hoping I’ll be able to help answer over the next few years”, she says.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

SDRC MEMBER PUBLICATIONS ROUNDUP

SDRC Member Publications Roundup for the 2019 Winter Quarter

The SDRC is proud to highlight groundbreaking publications from members for the 2019 Winter Quarter. SDRC supports multidisciplinary, collaborative research by providing a robust infrastructure that nurtures a thriving exchange of ideas, active discussion and collaborations. SDRC investigators have access to core facility services, training and enrichment programs, and a flourishing network of researchers. The SDRC also has a pilot and feasibility grant program that supports young investigators and trainees financially. Here, we list some of the SDRC-supported publications from our outstanding members.

1. Wiromrat P, Bjornstad P, Vijnovskis C, Chung LT, Roncal C, Pyle L, Lanaspa MA, Johnson RJ, Cherney DZ, Reznick-Lipina TK, Bishop F, Maahs DM, Wadwa RP. Elevated copeptin, arterial stiffness, and elevated albumin excretion in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2019. Epub ahead of print.

2. Nagy N, Sunkari VG, Kaber G, Hasbun S, Lam DN, Speake C, Sanda S, McLaughlin TL, Wight TN, Long SR, Bollyky PL. Hylauronan levels are increased systemically in human type 2 but not type 1 diabetes independently of glycemic control. Matrix Biol. 2019. 80:46-58.

3. Kahkoska AR, Adair LA, Aiello AE, Burger KS, Buse JB, Crandell J, Maahs DM, Nguyen CT, Kosorok MR, Mayer-Davis EJ. Identification of clinically relevant dysglycemia phenotypes based on continuous glucose monitoring data from youth with type 1 diabetes and elevated hemoglobin A1c. Pediatr Diabetes 2019. 20(5):556-566.

4. Wiromrat P, Bjornstad P, Roncal C, Pyle L, Johnson RJ, Cherney DZ, Lipina T, Bishop F, Maahs DM, Wadwa RP. Serum uromodulin is associated with urinary albumin excretion in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 2019. 33(9):648-650.

5. Shahbazi M, Cundiff P, Zhou W, Lee P, Patel A, D’Souza SL, Abbasi F, Quertermous T, Knowles JW. The role of insulin as a key regulator of seeding, proliferation, and mRNA transcription of human pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019. 10(1):228.

6. Kim D, Li AA, Cholankeril G, Kim SH, Ingelsson E, Knowles JW, Harrington RA, Ahmed A. Trends in overall, cardiovascular and cancer-related mortality among individuals with diabetes reported on death certificates in the United States between 2007 and 2017. Diabetologia 2019. 62(7):1185-1194.

7. Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D, Lum JW, Buckingham BA, Kudva YC, Laffel LM, Levy CJ, Pinsker JE, Wadwa RP, Dassau E, Doyle FJ (III). Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. NJEM 2019. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1907863.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

SDRC Member Publications Roundup

The SDRC has a superb team of talented investigators committed to developing novel therapeutic strategies for diabetes. The SDRC promotes collaborations among its members and with other institutions through robust enrichment programs, core services and financial support via pilot and feasibility grants. We are proud to list some of the innovative research findings published by our researchers (in bold) that were directly supported by the SDRC.

Nagy N, Gurevich I, Kuipers HF, Ruppert SM, Marshall PL, Xie BJ, Sun W, Malkovskiy AV, Rajadas J, Grandoch M, Fischer JW, Frymoyer AR, Kaber G, Bollyky PL. J Biol Chem. 2019 May 10;294(19):7864-787

Tikkanen E, Gustafsson S, Knowles JW, Perez M, Burgess S, Ingelsson E. Body composition and atrial fibrillation: a Mendelian randomization study. Eur Heart J. 2019 Apr 21;40(16):1277-1282.

Zanetti D, Rao A, Gustafsson S, Assimes TL, Montgomery SB, Ingelsson E. Identification of 22 novel loci associated with urinary biomarkers of albumin, sodium, and potassium excretion. Kidney Int. 2019 May;95(5):1197-1208.

Kahkoska AR, Adair LA, Aiello AE, Burger KS, Buse JB, Crandell J, Maahs DM, Nguyen CT, Kosorok MR, Mayer-Davis EJ. Identification of clinically relevant dysglycemia phenotypes based on continuous glucose monitoring data from youth with type 1 diabetes and elevated hemoglobin A1c. Pediatr Diabetes. 2019 Aug;20(5):556-566. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12856.

Lee WH, Ong SG, Zhou Y, Tian L, Bae HR, Baker N, Whitlatch A, Mohammadi L, Guo H, Nadeau KC, Springer ML, Schick SF, Bhatnagar A, Wu JC. Modeling Cardiovascular Risks of E-Cigarettes With Human-Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Endothelial Cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Jun 4;73(21):2722-2737.

Kim SH, Abbasi F. Myths about Insulin Resistance: Tribute to Gerald Reaven. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2019 Mar;34(1):47-52.

Harati H, Zanetti D, Rao A, Gustafsson S, Perez M, Ingelsson E, Knowles JW. No evidence of a causal association of type 2 diabetes and glucose metabolism with atrial fibrillation. Diabetologia. 2019 May;62(5):800-804.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

Nutritional Guidelines and Diabetes: A conversation with Dr. Christopher Gardner

Dr. Christopher D. Gardner has a PhD in Nutrition Science and is a Professor at the Stanford School of Medicine and the Director of the Clinical and Translational Research Core in the Stanford Diabetes Research Center. His work focuses on the study of dietary strategies and their impact on participant health outcomes such as weight, insulin and glucose dynamics and related parameters. He recently spoke at the 79th American Diabetes Association (ADA) Meeting in San Francisco on the role of nutrition in diabetes prevention. Dr. Gardner sat down with us to talk about the nutritional guidelines from the Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2019 report by the ADA and his recommendations.

What changes that were made to the American Diabetes Association nutritional guidelines this year stand out to you? What triggered those changes?

I would say there were three in particular.

The first was the decision to take on dietary patterns by looking beyond “food” and focusing on “food patterns”. By this, I am referring to diets such as Mediterranean, Vegan, Asian, Paleo, Low-Fat or Low-Carb which represent emphases on specific food groups rather than individual foods. The advantage of making suggestions based on food patterns is that they are more generalizable and adaptable. On the other hand, food patterns tend to be less specific and harder to follow for people who are looking for more structure in their diet. The new guidelines reflect consensus across different food patterns in its summary statements and encourages intake of vegetables and whole grains while minimizing processed foods and added sugars. Because of the emphasis on reducing added sugar and refined grains, this approach suggests a much lower overall carbohydrate intake which is corroborated by a growing body of evidence for the benefits of lower carbohydrate diets on glycemic control.

The second related point that stood out to me from the recent update in the guidelines was the shift to taking a stronger positive stance on lowER carbohydrate diets. I emphasize the “ER” portion of the term because there remains little consensus on “how low is low” when it comes to carbohydrates. Although a considerable body of evidence supports the benefits of low-carbohydrate diets for glycemic control, there is a paucity of data on whether low-carbohydrate diets have a significant benefit for long-term morbidity or mortality. All the available data for this outcome comes from “Low-Fat” studies. Unfortunately, diet studies with morbidity and mortality outcomes are challenging to fund and take many years to conduct. This was acknowledged in the newly released Consensus statement.

Thirdly, the panel was tasked with addressing pre-diabetes. This was in contrast to previous reports which restricted their work to Type I and II diabetes. However, current trends suggest that unless an emphasis is placed on preventing people from becoming diabetic, an unprecedented number of humans are likely to have the disease in the near future. The group of people with pre-diabetes is most likely to make that transition soon and is therefore the focus of the effort to prevent diabetes.

One ADA recommendation is to encourage diabetics to reduce their consumption of sugar sweetened beverages. In this context, what is your view of the effectiveness of the so-called 'soda tax' on changing consumer behavior?

Preliminary data from Berkeley and Mexico – two of the first to implement soda taxes – supports a benefit in terms of influencing consumer behaviors. A definitive answer in the area of health benefits will not be available any time soon. That is because the time frame of studying stability or change in human behavior can be very brief, whereas tracking the health impacts of those behavioral changes (e.g., morbidity, mortality) is a very extensive and intensive undertaking.

For people who consume foods sweetened with non-nutritive sweeteners in lieu of sugar-sweetened foods, what are some of the risks of non-nutritive sweeteners?

The major problem with the consumption of beverages sweetened with non-nutritive sweeteners is the issue of “compensation” – psychological and physiological. The psychological compensation may come from choosing a diet soda rather than a regular soda for lunch and feeling so good about that choice that the person might reward themselves with a sweet treat for dessert that they may not have consumed otherwise. In this case, the sugar and calories from the cake likely diminish or even negate the benefit of the diet soda. The physiological compensation may plausibly come from the body sensing that an incoming sensation of sweetness would be linked with a proportional level of caloric intake that in fact isn’t there. This in turn potentially leads to sub optimal food choices in the future. In addition, chronic consumption of artificial sweeteners could be linked to an increased obesity and type 2 diabetes risk. That said, it is important to note that many of these potential risks have not been proven and are currently plausible rather than definitive.

What, in your experience, is the most common problem diabetic patients face with respect to nutrition?

Although I don’t see patients, my sense is that the most common problem stems from focusing on carbohydrate counting without simultaneously developing a full appreciation of the variability in quantity and quality of carbohydrates across a wide range of food groups – vegetables, nuts and seeds, fruits, whole intact grains. In the past the focus has been on what NOT to eat, rather than also providing guidance on what to include.

The guidelines mostly focus on recommendations for Type 2 diabetics, saying 'There is inadequate research in type 1 diabetes to support one eating plan over another at this time'. Given that type 1 diabetes often has an onset in childhood, do you anticipate there being significant differences in nutrition guidelines for type 1 diabetics?

While there may be certain circumstances that lead to a need for separate dietary guidelines for type 1 vs. type 2 diabetes, in general the broad characteristics of a healthy diet for people with type 1 diabetes is are more similar than different for those with type 2 diabetes.

Dr. Gardner has worked tirelessly over the past 20 years to improve our understanding of the role of nutrition and dietary strategies in the management of diabetes and educate the public on good dietary practices. He also studies the impact of social factors such as the climate change movement and animal welfare concerns that could help people make positive dietary changes. He was instrumental in helping draft the nutritional guidelines section of the American Diabetes Association report on Diabetes Care.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

SDRC Member Spotlight: Nadine Nagy

Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC) member Dr. Nadine Nagy has a mission. She wants to stop type 1 diabetes (T1D) before it starts. By the time an individual is diagnosed with T1D, the damage is usually already done. The precious population of insulin producing beta-cells is scattered in tiny clusters, called islets, throughout the pancreas. Islets are tasked with the job of producing the body’s entire supply of insulin. In the setting of T1D which is an autoimmune disease, islets are attacked by the body’s own immune system, leaving the body unable to meet its own insulin demands. But what if there is a way to stop the immune system from launching an attack on the beta-cells in the first place?

Addressing this question and developing tools to prevent T1D forms the foundation of Dr. Nagy’s research at Stanford. In 2015, she and her mentor Dr. Paul Bollyky showed that a drug called Hymecromone or 4-methylumbelliferone (4-MU) protects beta-cells from autoimmune destruction by reducing the synthesis of hyaluronan in a mouse model of T1D. Hyaluronan is a major component of the extracellular matrix (ECM), a supportive structure, found in all tissues. Interestingly, hyaluronan is massively upregulated in disease, and it seems to be a supporting factor for rogue immune cells to destroy pancreatic beta-cells in T1D. Thus, an immune-mediated attack on the beta-cells may be averted by inhibiting hyaluronan production.

“I was always fascinated by the diverse structure and function of the ECM and especially hyaluronan, a simple molecule which has a major impact in disease. We realized early on that there are massive changes in the ECM that precede the onset of diabetes and that disease prevention is a real possibility” says Dr. Nagy.

Dr. Nagy and her colleagues observed for the first time a build-up of hyaluronan in the pancreatic tissues of younger T1D donors obtained from the Network of Pancreatic Organ Donors (nPOD), who had the disease for less than 5 years. In the years following this discovery, Dr. Nagy used mouse models that spontaneously developed T1D to prove her hypothesis that the presence of hyaluronan was essential in facilitating the immune system to mount an attack on the pancreatic beta-cells. Her work revealed that hyaluronan impairs the induction of a class of immune cells called regulatory T cells or Tregs which restrain another group of immune cells called cytotoxic T cells from killing healthy pancreatic beta cells.

Dr. Nagy found that 4-MU treatment spared the beta-cells from destruction by inhibiting hyaluronan synthesis and allowing T-regs to control the aggressive cytotoxic T-cells. As a potential early therapeutic intervention for T1D, 4-MU tips the balance between tolerance and destruction by using the body’s own immune system to control the progression of the disease.

In 2016, Dr. Nagy was awarded a pilot and feasibility award from the SDRC to develop 4-MU analogs to pursue her goal of preventing T1D. The grant enabled her to publish her findings on hyaluronan’s role in autoimmunity and inflammation, making a strong case for pursuing 4-MU as a potential therapeutic. As a drug, 4-MU has been in clinical use for over 4 decades in European and Asian countries for treating biliary spasms and has an excellent safety profile. However, 4-MU has poor pharmacokinetics, and a low bioavailability, hence low utility as a drug in its current form. Once ingested, 4-MU rapidly breaks down into its metabolites. Dr. Nagy’s recent studies found that 4-MU and its main metabolite 4-MUG exist in equilibrium in the body and that both are capable of inhibiting hyaluronan synthesis.

Dr. Nagy is optimistic about the potential to repurpose 4-MU as a drug to prevent T1D in newly diagnosed or at-risk populations. However, she acknowledges, there is still a lot of work that needs to be done before we see 4-MU in the clinic. “I would like to see our translational work moving forward into clinical trials. I believe using 4-MU has the potential to prevent T1D”, she says.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

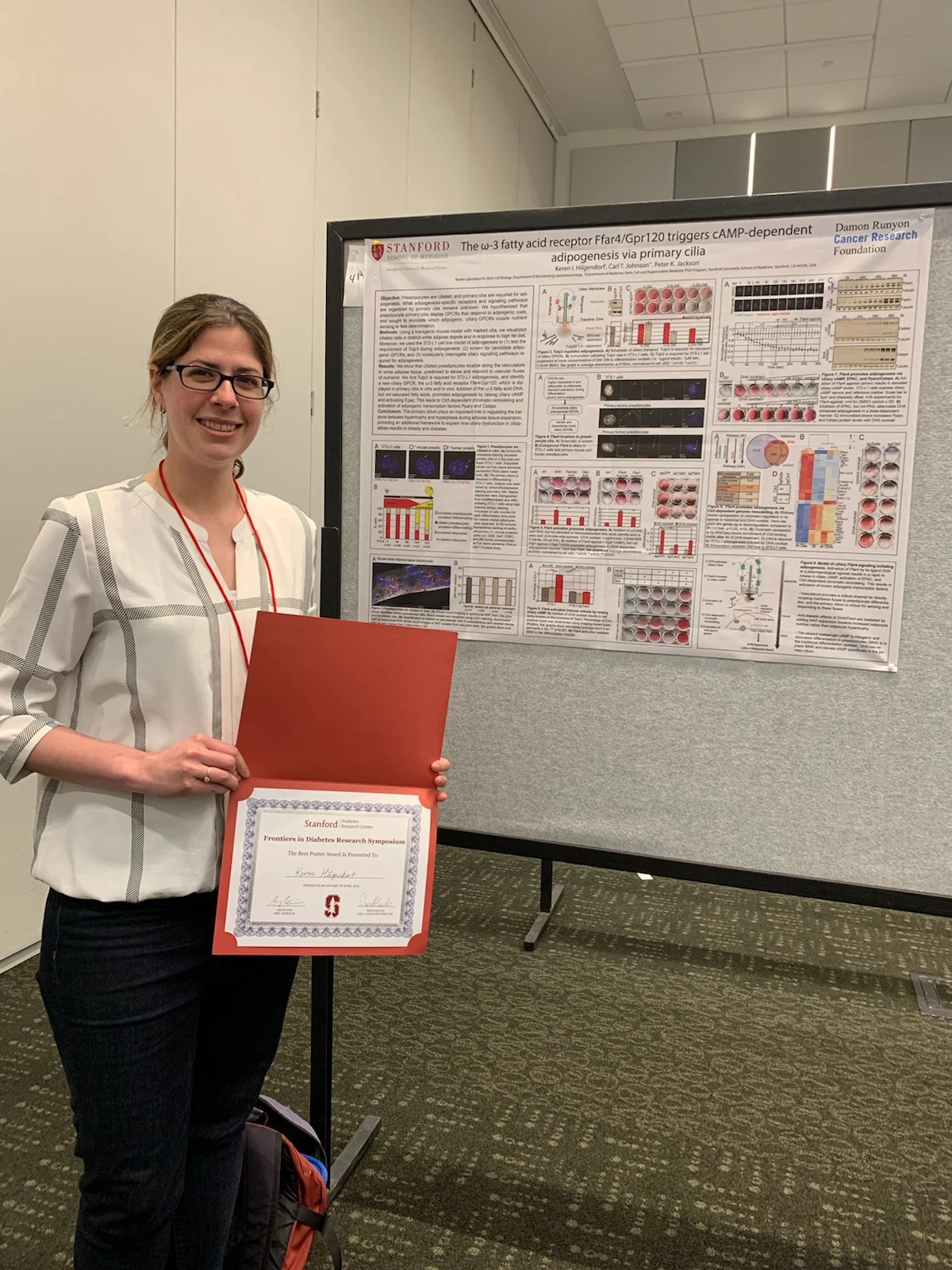

SDRC Trainee Highlight

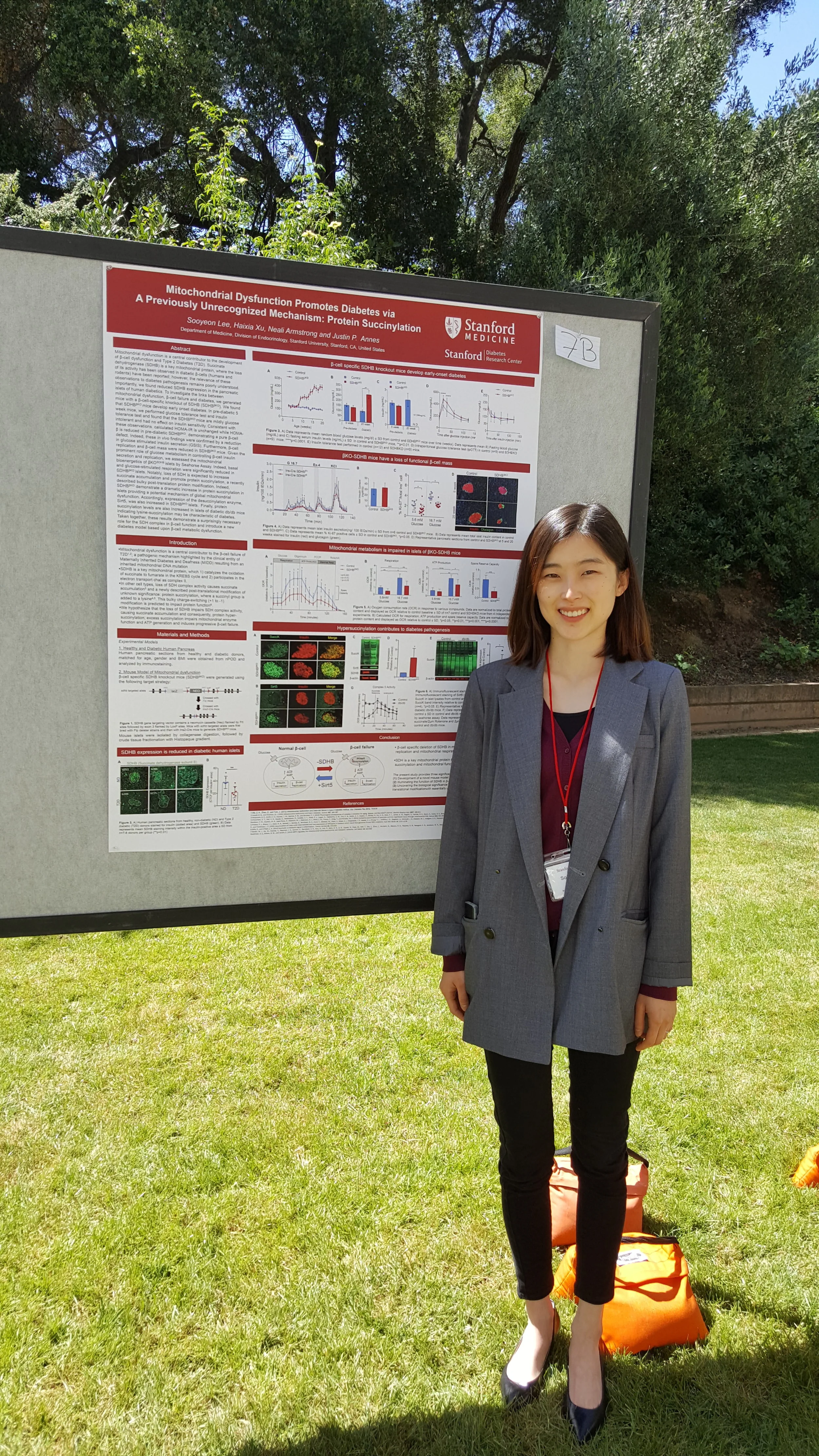

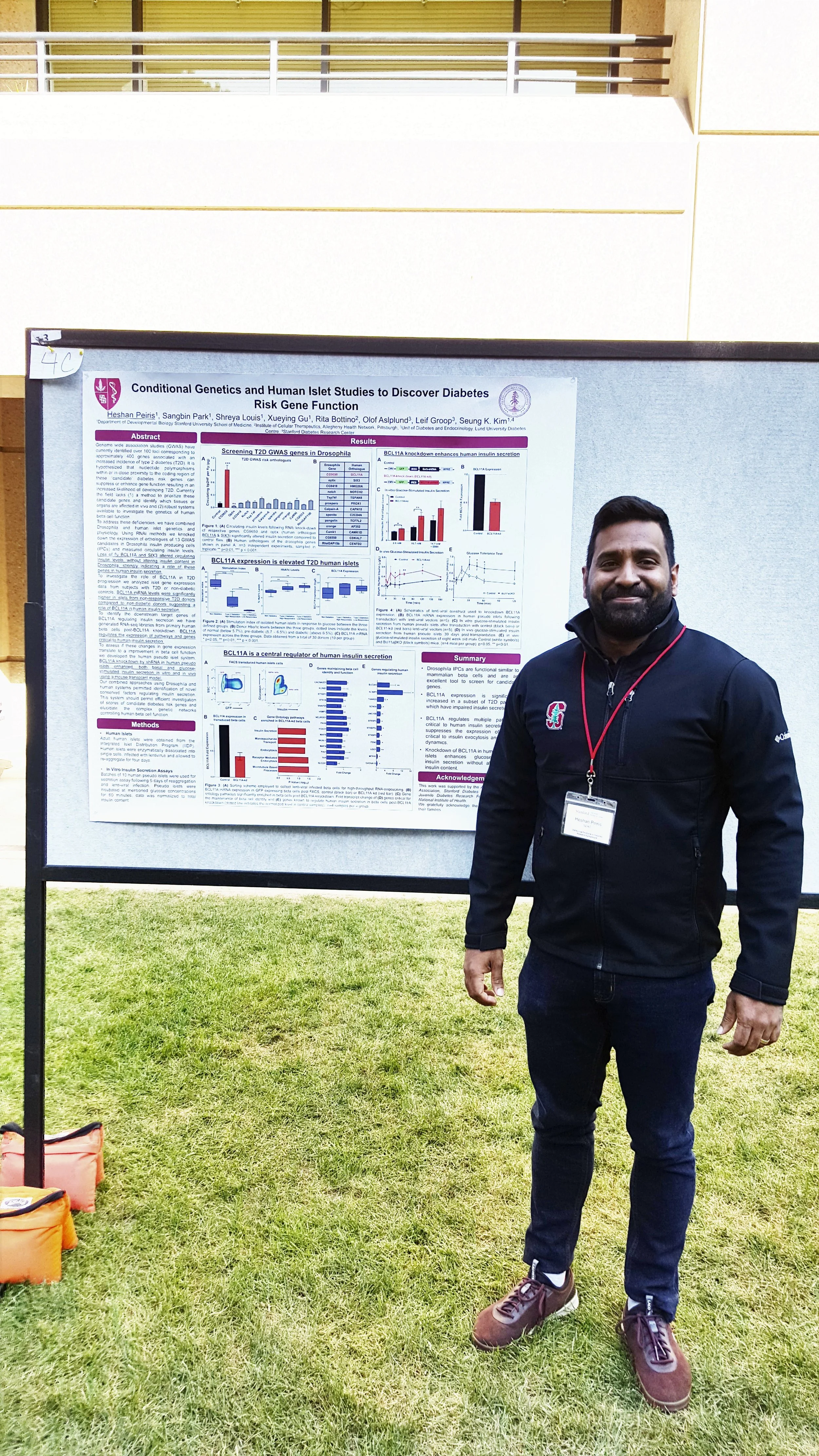

The SDRC is proud to highlight the research achievements of its trainees by presenting outstanding poster awards during its 4th Annual Frontiers in Diabetes Symposium.

Dr. Keren Ita Hilgendorf’s work focuses on understanding the function of a sensory organelle called the cilium on fat cell development and its role in metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes. Explaining her focus on cilia, she says, “I have always been interested in understanding how key disease signaling pathways work on a molecular level. The primary cilium is an ancient and spatially distinct antenna-like protrusion that has emerged as a central sensory organelle of the cell. Patients with dysfunctional ciliary signaling present with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations, including obesity and diabetes.” Her study provides a molecular framework to explain how the primary cilium regulates the formation of fat cells from fat cell precursors by identifying a novel ciliary receptor which is activated by omega-3 fatty acids, known to have anti-diabetic effects.

Dr. Hilgendorf used a mouse model which permitted visualization of cilia in fat tissue after the mice were fed a high-fat diet and showed that the ciliated fat precursor cells position themselves close to blood vessels and are thus able to quickly respond to changes in nutrient cues in the blood through proteins called receptors on the cilia. To identify signaling pathways involved in adipogenesis or the generation of fat cells from their precursors, Dr. Hilgendorf screened candidates in fat precursor cells grown in a dish enabling her to identify Ffar4, a novel free fatty acid ciliary receptor that responds to omega-3 fatty acids. Dr. Hilgendorf notes, “Human mutations in the Ffar4 gene have been linked to childhood obesity. Patients with dysfunctional ciliary signaling are obese and diabetic, and fat precursor cells isolated from obese humans are shortened and signaling-defective”, suggesting that she has identified a central pathway that has gone awry in obese and diabetic individuals. However, acknowledging that other signals likely also factor into the molecular dysfunction underlying obesity and diabetes, she notes “The integration of multiple ciliary signaling pathways may occur at the level of the primary cilium and we are actively pursuing this line of investigation”. Dr. Hilgendorf plans to use the SDRC poster prize money to attend the FASEB Cilia Conference this summer. She is a Research Scientist in SDRC member Dr. Peter Jackson’s group at Baxter Laboratories.

Research Scientist Dr. Owen Jiang and Postdoctoral scholar Dr. Yunshin Jung explore the mechanisms by which brown fat tissues provide metabolic benefits to the body. Brown fat is classically known for its heat generating capabilities which burns calories and contributes to weight loss. However, recent studies show that brown fat also secretes factors that help with blood sugar homeostasis. Drs. Jiang and Jung’s work identified one such secreted protein called Isthmin-1 (ISM1) which improves the ability of fat cells to take up glucose. “Initially, we were looking for secreted proteins that were both hormone-like and enriched in brown fat cells. This gave us 16 candidates, including Isthmin-1 which is expressed in brown fat”, they explained. Their subsequent analyses demonstrated that ISM1 induced glucose uptake by fat cells via an insulin-independent mechanism.

When mice fed with a high-fat diet are treated with ISM1, they display a long-term improvement in insulin sensitivity and glucose uptake. Interestingly, unlike insulin treatment, ISM1 treatment improves blood glucose levels without a concomitant increase in fat accumulation in peripheral tissues like the liver. Drs. Jiang and Jung found that ISM1 shuts down the molecular pathways that drive fat accumulation in the liver in these mice. The researchers are now developing even more sensitive assays to permit them to detect ISM1 in blood. “We have exciting preliminary data suggesting that our ISM1 assay can detect picogram levels of ISM1”, they note.

In terms of how their work is relevant to current and future therapeutic strategies combating diabetes and obesity, they are optimistic. “This could potentially become a recombinant protein therapy for patients with diabetes and insulin resistance”, they say. The power of ISM1 lies in the fact that although it activates a prominent signaling mechanism called the PI3K/AKT pathway in target cells which promotes glucose uptake, it does so without accumulating fat. The researchers plan to test the function of ISM1 in fat cell development and assess its role in human obesity in the future. Drs. Owen Jiang and Yunshin Jung are in Dr. Katrin Svensson’s group in the Department of Pathology at Stanford. They plan to use their SDRC poster prize money to cover travel expenses to conferences.

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

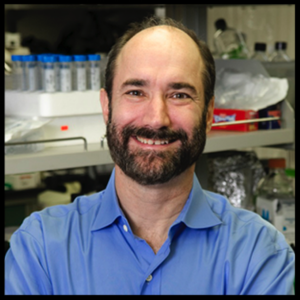

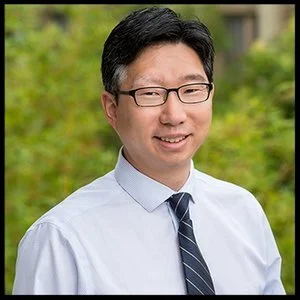

Fire without smoke? E-cigarettes may impair blood vessel health even without nicotine

Dr. Joseph Wu

In 2015, the British Government issued a press release stating that electronic cigarettes or e-cigarettes were around 95% less harmful than smoking based on an independent Public Health England expert report. Recent groundbreaking research published by Stanford Diabetes Research Center (SDRC) member Dr. Joseph Wu and his colleagues, Dr. Won Lee, PhD and Dr. Sang-Ging Ong, PhD in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC) in June 2019 is the latest in a series of studies to challenge the claim that vaping is safer than smoking.

Vaping refers to the inhalation and exhalation of vapors produced by heating a flavored liquid containing nicotine in a device called an e-cigarette. Often, smokers who want to kick the habit take up vaping as it has been marketed as a safer alternative that has fewer toxic chemicals than regular cigarettes. Conventional cigarette sales and consumption have been on a steady decline in the US, whereas, e-cigarette use has been on the rise, especially among youth. While e-cigarettes do have a lower content of many of the chemicals found in traditional cigarettes, the current study suggests that certain flavoring liquids in e-cigarettes may severely damage the inner lining of blood vessels and increase cardiovascular disease risk even in the absence of nicotine.

Dr. Wu’s team studied the effect of 6 popular flavors of e-liquids on the health and integrity of endothelial cells which form the inner lining of blood vessels. Endothelial cells are vital for cardiovascular health and their degradation is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk. Using a novel approach, the researchers generated endothelial cells for this first-of-its-kind study from induced pluripotent stem cells or iPS cells. Under the right laboratory conditions, iPS cells can be coaxed to become any cell type in the body including endothelial cells. This enabled the researchers to have a ready pool of endothelial cells on which to test e-liquids.

Dr. Wu found that all 6 flavors of e-liquids had detrimental effects to varying degrees on the endothelial cells, however, exposing the cells to menthol and cinnamon flavored e-liquids had the most dramatic effects in terms of decreasing their ability to survive, form vascular tubes and migrate. Surprisingly, these effects did not appear to be correlated with the presence or absence of nicotine in the e-liquids, suggesting that the flavoring chemicals themselves were toxic. In addition, the researchers found that exposing endothelial cells to blood taken from smokers or vapers after consuming a single e-cigarette or cigarette was sufficient to impair their function and increase the production of free radicals and molecules associated with cell death and inflammation.

The endothelial cells displayed other signs of damage as well, some of which were dependent on nicotine levels. The scientists noted that exposure of endothelial cells to nicotine containing e-liquids increased their uptake of inflammation-associated lipids and low-density lipoproteins and activated inflammatory immune cells called macrophages. Moreover, the team observed similar levels of nicotine in the blood of participants immediately after vaping or smoking.

“It is important for e-cigarette users to realize that these chemicals are circulating within their bodies and affecting their vascular health”, says Dr. Wu in a Stanford News Press Release. Dr. Wu and his colleagues acknowledge caveats in their study including the fact that they tested unheated e-liquids as opposed to the aerosols and their analyses being limited to just six of the hundreds of e-cigarette flavorings available in the market, precluding the universal extrapolation of their results to all e-cigarettes.

Describing the relevance of the study in an audio summary, JACC Editor-in-Chief Dr. Valentin Fuster said, “Although it has been portrayed that e-cigarettes can be beneficial in smoking cessation, there is growing alarm at the rate of use among teens and adults and increasing concerns that e-cigarette products are in fact a gateway to future tobacco use”. Moreover, he added, advertising promotes e-cigarette flavors targeting children and young adults – flavors that could be toxic as shown by Dr. Wu’s team.

Dr. Fuster concluded his remarks by citing an editorial comment on the study in the same issue of JACC by Drs. Freedman and Trivedi from the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Worcester, Massachusetts in which they write “The results by Lee et al clearly demonstrate that e-liquid flavorings had stronger effects on cytotoxicity, vascular dysfunction and angiogenesis than nicotine. Thus, in addition to harm from the nicotine, the additives are a potential source of adverse vascular health and one that is being disproportionately placed on the young”. It appears, he said, that even without the smoke of combustible cigarette products, there may be a smoldering fire of adverse health effects.

Dr. Won Lee, now an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, was the recipient of a Pilot award from the SDRC from a grant sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Sang-Ging Ong is an assistant professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago. Other Stanford coauthors include research assistant Yang Zhou, postdoctoral scholars Dr. Lei Tian, Dr. Hongchao Guo, graduate student Hye Ryeong Bae, undergraduate student Natalie Baker and Professor Kari Nadeau, MD, PhD, Department of Pediatrics, Stanford.

Dr. Won Lee

Dr. Sang-Ging Ong

By

Harini Chakravarthy

Harini Chakravarthy is a science writer for the Stanford Diabetes Research Center.

Celebrate MARCH AS National Nutrition Month with ‘Feel Good Food’

SDRC is committed in its mission to empower diabetics and their families through its support of Stanford’s Diabetes Care Program and their efforts to provide a nurturing community for diabetics.

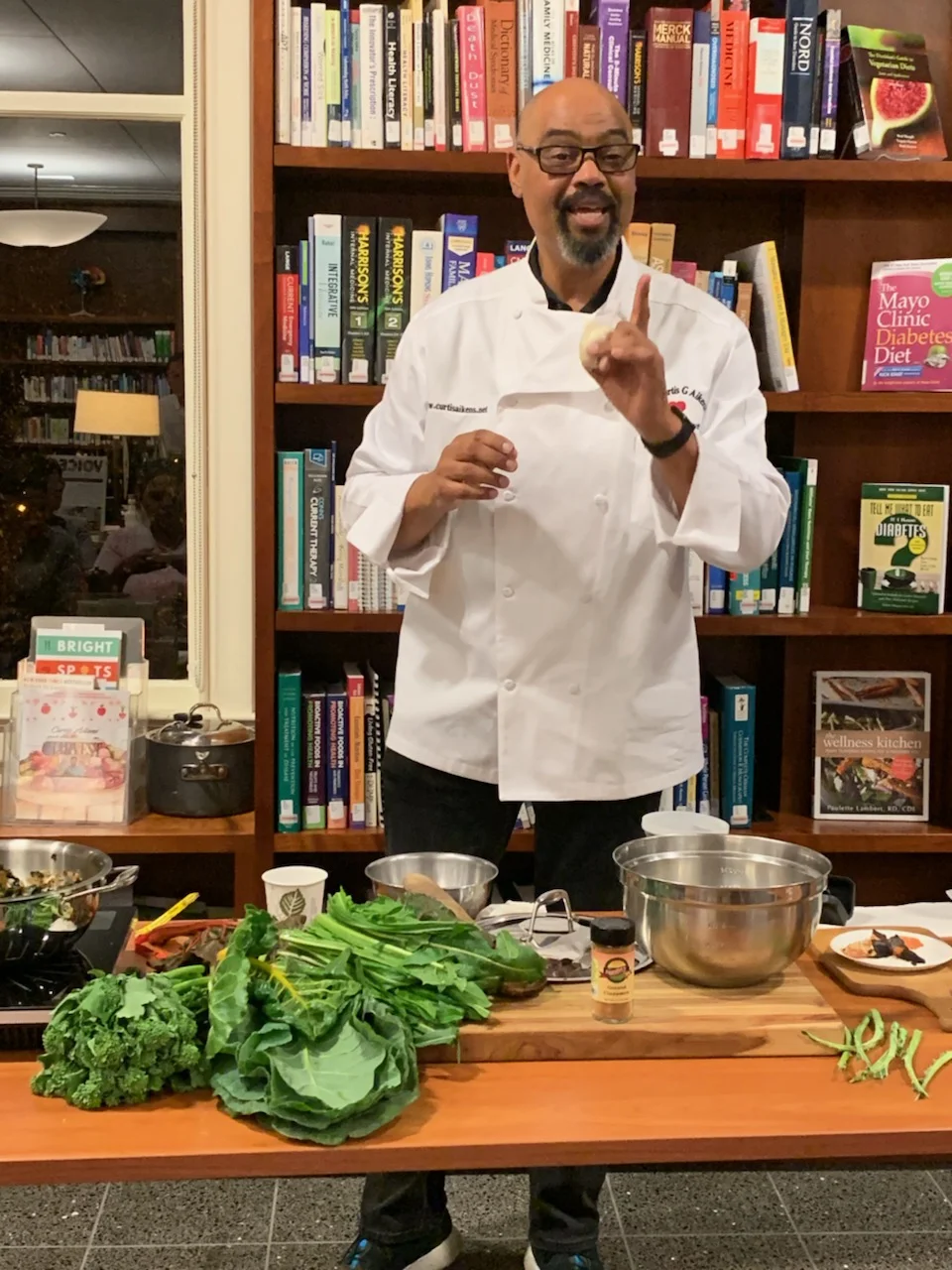

SDRC is committed in its mission to empower diabetics and their families through its support of Stanford’s Diabetes Care Program and their efforts to provide a nurturing community for diabetics. Eating healthy can be difficult and even stressful for many of us. For diabetics who balance their nutritional needs with maintaining their blood glucose levels on a daily basis, it can feel like a daunting challenge. The Stanford Diabetes Care Program aims to educate participants and their families about healthy, easy and delicious food choices through its popular ‘Feel Good Food’ events with noted Chefs including Chef Curtis Aikens (see picture). At the end of the events, the Chef provided easy-to-cook recipes that incorporated fresh, healthy and easily obtained ingredients.

One of the key points that the Chef emphasized was to realize that any recipe can be tailored to fit one’s needs. He reiterated the importance of eating the food that makes one feel good, while also controlling portion sizes. Through his presentation, Chef Aikens encouraged participants to try new recipes and channel their creativity towards creating good food that they would love. He gave examples of healthy and natural sources of nutrients such as kale, sweet potatoes, pinto beans, eggs, apples, oranges and even chocolate and suggested food combinations that maximized their health benefits and taste. Most importantly, Chef Aikens wants people, diabetics and non-diabetics alike, to recognize that healthy cooking and eating can be a wonderful way to promote relaxation and self-care.

On the eve of National Nutrition Month, we provide some recipes that Chef Aikens shared with the participants at the Stanford Diabetes Care Program events. Feel free to improvise!

WINTER SQUASH SOUP

Ingredients:

1 medium Winter Squash (Kabocha, Butternut, Acorn or Pumpkin)

1 medium Leek

1 medium Carrots

1 stalk Celery

2 Quarts of Chicken Stock

3 tbsp. Butter or Olive oil

Salt and pepper to taste

Method:

Split squash and remove seeds or use 2 cups of pre-cut winter squash.

Roast squash in a 350 degrees oven for 30 minutes and let cool.

Sauté diced carrot, leek and celery in 3 tbsp of butter.

Scoop roasted squash out of its skin and add to sautéed vegetables.

Cover vegetable mixture with 2 quarts of chicken stock or water on low heat for 30 minutes.

Blend in standard blender or use immersion blender and season with salt and pepper to taste.

Consider serving with a topping of roasted pumpkin seeds, sunflower seeds, and/or a drizzle of plain yogurt for garnish

EZ GREENS

Greens are great and easy to make! Kale, mustard, turnip, collard and Swiss (chard) are all fabulous greens! All can be prepared using this simple, quick easy method, except collards, which take a little longer to cook! However, here is a trick for you that will allow you to have the greens of your choice on your table in about 20 minutes.... Recipe serves 2.

Ingredients:

1 bunch Kale (curly kale) removed from stem

1 small onion diced

2 Tbsp oil

3/4 Cup water

Salt & pepper to taste

Method:

Add oil to medium sauce pot heat.

Add onion and cook for 3 to 5 minutes.

Add Kale, cook with a lid for about 1 to 2 minutes. Stir 1- or 2-times replacing lid after each stir.

Add water and drizzle just a bit of oil on greens. Season with salt and pepper. Place lid back on pot and cook on low heat.

Variations:

The above recipe can be used with a variation of Greens including: Collard greens, Dandelion, Kale and Swiss chard

To add protein in this dish you can add 1/2 cup of finely chopped Pancetta to the greens.

Sauté onion and Pancetta in the pan with oil.

Add the bunch of greens with the sautéed onions and Pancetta and place the mixture on low heat.

To add a different flavor to the greens you can add 2 cloves of garlic to the recipe.

CHOCOLATE DIPPED ORANGES

Ingredients:

2 large oranges, peeled

1 cup dark chocolate chips (dairy-free chips to keep vegan)

1 tsp canola oil

Method:

Peel the oranges and arrange them on a lined sheet (I use a silpat, but parchment paper also works). If any are wet, use a paper towel to pat them dry. Chocolate will not adhere to the wet parts of the orange

Combine 1 tsp of Canola oil with 1 cup of Dark Chocolate Chips either in a heat-safe bowl or over a double boiler.

Melt in a heat-safe bowl or a double boiler (using medium low heat) or by 30-second intervals in the microwave.